For the month of April I am participating for the ninth time in the annual A-to-Z blogging challenge, writing a post for every letter of the alphabet. My theme this year is the world, the world that is always with us, that we must not keep out and cannot do without.

For the month of April I am participating for the ninth time in the annual A-to-Z blogging challenge, writing a post for every letter of the alphabet. My theme this year is the world, the world that is always with us, that we must not keep out and cannot do without.

A thing becomes visible not only when it is in sight, but also when it is seen. Or conversely, something is invisible either because it is hidden or because it is not looked at. Let me elaborate.

In the summer of 1996 I happened to be in England with my husband and our son, then eleven, during the Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S.A.). It was there that I was first struck by the difference between the British and the U.S. coverage of the Games. Britain certainly covered the relatively few events in which one of its athletes had a chance of winning a medal (I refuse to use the horrible verb “medaling”), but it also covered plenty of other events of interest to its viewers. By contrast, the U.S. coverage of the Olympics is obsessed with the U.S. winning the maximum number of medals and with besting its competitors, particularly those in the political arena. If there is a sport in which another country, however small, is pre-eminent, the U.S. is determined to beat it, despite the fact that it already takes home the most medals by far of any other country.

In the summer of 1996 I happened to be in England with my husband and our son, then eleven, during the Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S.A.). It was there that I was first struck by the difference between the British and the U.S. coverage of the Games. Britain certainly covered the relatively few events in which one of its athletes had a chance of winning a medal (I refuse to use the horrible verb “medaling”), but it also covered plenty of other events of interest to its viewers. By contrast, the U.S. coverage of the Olympics is obsessed with the U.S. winning the maximum number of medals and with besting its competitors, particularly those in the political arena. If there is a sport in which another country, however small, is pre-eminent, the U.S. is determined to beat it, despite the fact that it already takes home the most medals by far of any other country.

In an interesting study, Framing the Olympic Games (2008), authors Caroline Walters and Sheila Murphy investigated this very subject—the way that the U.S. television coverage of the Games presents them in an ultra-competitive and nationalistic frame. They write: “While media outlets from all countries are guilty of reporting on the Olympics (as well as other international events) from their own perspective, the American media have been routinely criticized for their overly nationalistic coverage (78). Given this skewed coverage, which the authors amply demonstrate, they asked whether and how it had an impact on the way American viewers see the Games.

Could the American media’s nationalistic portrayal of the Olympic Games ultimately undercut the very purpose of the event? . . .[W]e examined whether—far from promoting world peace—adopting a competitive and nationalistically-centered frame for Olympic coverage actually serves to reinforce international rivalry and undercuts the intended objectives of the IOC.” (84)

Walters and Murphy’s results suggested that “nationalistically framed Olympic broadcasts may encourage viewers to be less engaged and open to cooperation with other countries” (99). They concluded:

This research exposes a contradiction between how the modern Olympics Games are currently being presented to the American public and the official mission of the IOC. Our results reveal important and potentially alarming consequences of the use of highly nationalistic framing with respect to the Olympic Games, and perhaps international events more generally. These findings make a strong argument for the need to reframe or at least soften American television coverage of the Olympic Games. (100)

If the U.S. media’s framing of the Olympic Games may predispose American viewers to see their relationship with the rest of the world as one of competition rather than cooperation, what about the visibility of the rest of world in U.S. news coverage?

In its story, The world, according to the U.S. news, 1 Point 21 Interactive, a company that creates web content to increase awareness of particular brands or social issues, analyzes 94,000 U.S. news headlines from three news outlets, the New York Times, USA Today, and Fox News, between January 2019 and May 2023 to see which countries were mentioned the most and the least, and in what regard, and then they mapped the data visually.

In its story, The world, according to the U.S. news, 1 Point 21 Interactive, a company that creates web content to increase awareness of particular brands or social issues, analyzes 94,000 U.S. news headlines from three news outlets, the New York Times, USA Today, and Fox News, between January 2019 and May 2023 to see which countries were mentioned the most and the least, and in what regard, and then they mapped the data visually.

The piece began with the simple statement, “Our understanding of the word is shaped by the information we encounter – and the information we don’t.” It found that the countries that were mentioned the most were those that were most important to U.S. foreign policy and that “just 10 countries, including the U.S., accounted for 80% of all headlines that name a country”, with China, Russia, Iran, and Mexico in the top ten every year. Of the countries that were rarely mentioned, they found that they tended to make the headlines only if they had a war, a political crisis, or a natural disaster. Even so, if the country was small, or if it was in Sub-Saharan Africa, it was unlikely to get a mention.

It find it sad that U.S. news media rarely cover news from the rest of the world and even then, only in terms of how that news affects the United States. As a result, Americans are presented with a skewed and incomplete picture of the world. Funnily enough, it may be the people in the smaller, less powerful nations who have a more accurate view of the world. They certainly have to know much more about the United States than it knows about them.

These two examples of what the U.S. news media covers and on what basis demonstrate that we see what we are shown, what is made visible. The fact that so much is rendered invisible requires us to do more work to uncover and reveal it (Williams).

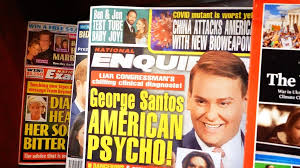

What about the case in which the news item is there, but we don’t see it, either because we have been given to understand that it is not important, or because our attention is directed elsewhere? How many times have you become interested in a subject—prisons, for example—and suddenly started seeing articles about it everywhere? It was there all along, hidden in plain sight, only you didn’t have the eyes to see it. Or perhaps society’s messaging about prisons and prisoners had taught you to avert your eyes when faced with the subject.

These reflections have been sparked in part by the Catch and Kill phenomenon brought to light by former president Donald Trump’s latest trial, in which his campaign paid the National Enquirer to buy a story about him (David Pecker, former publisher of the National Enquirer called in “checkbook journalism”) and then to kill it—to withhold publication. Of course this is an extreme case of visibility—or rather, invisibility. Although the story is true, it will not see the light of day.

postcard, Bread and Puppet Theater

What does this question of visibility have to do with the world? Well, what we see depends on where we stand, what we want to see, and how much digging we are prepared to do. There is much that is obscured, hidden between the lines and beneath the surface. Why should we want to see the world whole, and not blinkered by our nation’s perceived strategic interests? Well, that’s a question akin to “Why would we want to seek enlightenment?”

Perhaps it is enough to go back to the Olympic Games and the International Olympic Committee’s concept of the Olympic Truce, “which encourages all participating countries to lay down their weapons during the Games in an effort to create a window for dialogue, reconciliation, and diplomatic conflict resolution” (Walters & Murphy 77). Making the effort to create a window lets in light and opens up new possibilities where there was once a wall.

Let’s take off our blinkers and see the world whole. Our very survival may depend on it.

that would be great!

LikeLiked by 1 person