For the month of April I am participating for the ninth time in the annual A-to-Z blogging challenge, writing a post for every letter of the alphabet. My theme this year is the world, the world that is always with us, that we must not keep out and cannot do without.

For the month of April I am participating for the ninth time in the annual A-to-Z blogging challenge, writing a post for every letter of the alphabet. My theme this year is the world, the world that is always with us, that we must not keep out and cannot do without.

The university has been a fraught space in recent years, in the midst of conflict and controversy. Far from being seen as an ivory tower, where scholars talk to each other in a language no one else could understand, it now seems to be regarded as a hotbed of the radical left, where faculty plant dangerous ideas in the minds of impressionable students. A university education, even at public institutions, has got so expensive that many students emerge heavily in debt. Also in the United States, admissions programs that sought to redress the legacy of racism that has denied so many students a university education have been overturned by the Supreme Court. But I’m going to talk about something else altogether: the way universities open up the world, both to their students and to the surrounding community.

A university education is often evaluated on its ability to secure higher-paid jobs for its graduates. And at an average of $26,000/per year for public institutions and nearly $56,000/year for private ones, students and their parents are certainly entitled to demand tangible results. However, most people who have been to college or university know that it brings as many intangible benefits as it does measurable ones. One inestimable benefit of a university education is the way it opens up the world to the student. While narrower vocational and professional programs may prepare the student for a particular job, a university education prepares the student for life in its broadest sense. I can personally attest to this.

As a Harvard undergraduate in the early 1970s majoring in English and American literature and language, most of my classes focused on literature and culture from Britain and the U.S. However, I also had the rare opportunity to study the Sanskrit language and Vedanta philosophy. Ironically, our family had just immigrated from India, where I had not had been able to study Sanskrit in high school, but my U.S. university education allowed me to fill that gap.

Outside the classroom the university gave me the opportunity to learn about struggles for freedom unfolding around the world. In the Spring of 1972 a group of African American students occupied a building on campus calling for Harvard to divest stocks in Gulf Oil, which was providing important foreign exchange dollars for the Portuguese government in Angola. I joined other students who rallied outside the building in support of the same cause and of my courageous fellow-students.

Outside the classroom the university gave me the opportunity to learn about struggles for freedom unfolding around the world. In the Spring of 1972 a group of African American students occupied a building on campus calling for Harvard to divest stocks in Gulf Oil, which was providing important foreign exchange dollars for the Portuguese government in Angola. I joined other students who rallied outside the building in support of the same cause and of my courageous fellow-students.

Fifty years later, as another U.S.-funded war rages, college campuses are again engaged in divestment campaigns. On April 5th, 2024, The Harvard Divinity School Student Association passed a resolution urging the Harvard Management Company — which oversees Harvard’s $50.7 billion endowment — to divest from “weapons manufacturers, firms, academic programs, corporations, and all other institutions that aid the ongoing illegal occupation of Palestine and the genocide of Palestinians.” The previous week, on March 29, 2024, Harvard Law School’s Student Government passed a similar resolution. Today, on university campuses around the U.S., students are again calling for their institutions to divest their endowments from corporations that profit from the war in Gaza.

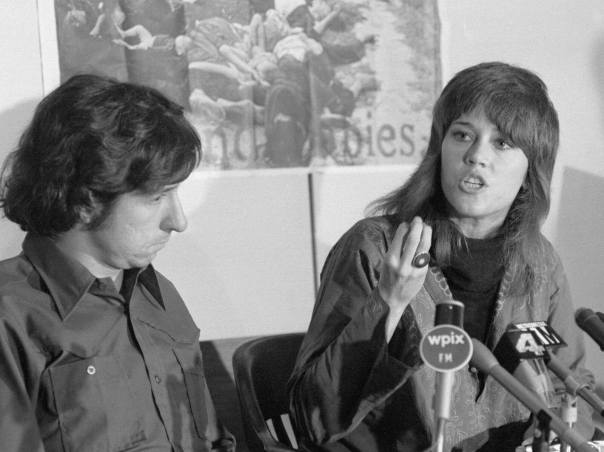

Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda, c. 1974-5

Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda, c. 1974-5

I remember Jane Fonda and her husband Tom Hayden speaking on campus back in 1974 or 1975 on behalf of their newly-formed Indochina Peace Campaign. They had both traveled to Vietnam, were strongly opposed to the Vietnam War, and had taken the decision to lobby Congress to deny military funding to then-President Nixon. To this end, Tom Hayden delivered a series of six lectures on American imperialism in the Capitol building itself. In April 1974, the House voted 177-154 to deny the President’s request for funding, and the Senate followed suit.

In the late 1980 and early 1990s, the University of Massachusetts brought the world to me. As a graduate student in postcolonial literature I had the extraordinary good fortune to study the African novel with the Nigerian “father of African literature” Chinua Achebe, while he was a visiting professor. During that time I was also able to hear the great Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene, South African Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer, Nigerian Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, South African writer Miriam Tlali, just to name a few world writers and artists who came to this large public university in our small New England town. The South African writers taught me a great deal about the system of apartheid and were active in the struggle against it.

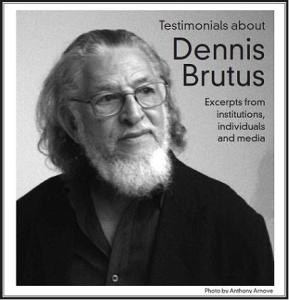

For years I taught at Worcester State in Central Massachusetts, a public university which had less funding available for bringing luminaries to campus. Nevertheless, we found ways to bring the wider world to our students, both in and out of the classroom. By this time I was a faculty member teaching world literature, postcolonial literature, and global studies. Our library housed the Dennis Brutus Collection, an archive of personal papers donated to the university by the South African poet-in-exile who came to campus more than once during my time there. Other campus visitors included the spokesperson for an indigenous tribe in Ecuador trying to save their forests and way of life, speakers on the root causes and prevention of genocide, learning from the tragedy of Rwanda, on favelas in Brazil, and on the global conflicts sparked by climate crisis. In addition to the more popular English-speaking destinations of Britain and Australia, faculty-led study abroad opportunities for our students included trips to India and to Central and South America—Ecuador, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua.

For years I taught at Worcester State in Central Massachusetts, a public university which had less funding available for bringing luminaries to campus. Nevertheless, we found ways to bring the wider world to our students, both in and out of the classroom. By this time I was a faculty member teaching world literature, postcolonial literature, and global studies. Our library housed the Dennis Brutus Collection, an archive of personal papers donated to the university by the South African poet-in-exile who came to campus more than once during my time there. Other campus visitors included the spokesperson for an indigenous tribe in Ecuador trying to save their forests and way of life, speakers on the root causes and prevention of genocide, learning from the tragedy of Rwanda, on favelas in Brazil, and on the global conflicts sparked by climate crisis. In addition to the more popular English-speaking destinations of Britain and Australia, faculty-led study abroad opportunities for our students included trips to India and to Central and South America—Ecuador, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua.

Sona Jobarteh and her band

It is not only the students who benefit from a university’s portal to the wider world; the surrounding community does as well. In retirement, we live in walking distance from the university campus, and the wealth of international events—lectures, musical performances, film series, plays—is staggering. Just two weeks ago, for instance we attended a free outdoor concert by the Gambian artist Sona Jobarteh, and over the years we have also attended concerts on campus by sitar maestro Ravi Shankar, sarod virtuoso Ali Akbar Khan, the great qawaali singer and composer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and the late great reggae singer Toots Hibbert of Toots and the Maytals. The UMass faculty includes eminent scholars and public intellectuals from around the world who give book talks and lectures, all of which are open to the public. Our own lives are enriched by the many graduate students from the Indian subcontinent.

According to 2022 campus data provided by UMass Amherst, in 2022, 7% of the 24,000 enrolled undergraduates come from outside the U.S.–1680 students; and, as of Fall 2023, 34% of the approximately 8000 graduate students—2,677 students from 101 different countries. If, in the current nativist political climate, some may balk at these figures, know that in many cases it is these students who help keep the university going. According to NAFSA: Association of International Educators, “Over one million international students contributed $40.1 billion to the U.S. economy in the 2022-2023 academic year,” and their economic activity supported 368,333 U.S. jobs. Beyond numbers, the engaged presence of these students helps to create a vibrant society, infusing the communities around the country with their ideas, inventions, and expertise.

On a personal level, international students and faculty whom I have met at UMass or at other universities over the years are now my dearest friends. They mean the world to me.

When I attended Wayne State University in Detroit from 1964-1968, the main interaction with the surrounding community was taking blocks and blocks to expand the university.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You were literally bringing the world to people’s doors–and connecting your own book learning with the needs and resources of the community. I was at a rally yesterday and took a photo of a lovely sign saying “The People’s University.” but couldn’t find a spot in the post to put it.

LikeLike

No, the university was erasing the community to build more buildings. They weren’t interested in interacting with the people, they just wanted them gone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aargh–still happening all over. And they don’t even pay taxes! But you were trying to do what a public university ought to be doing.

LikeLike

we live next door the University of Wollongong and while it may not have the breadth of visiting speakers your university has, we enjoy many gatherings on campus. We also enjoy using the gym and pool five days a week with a group of like minded people. You have inspired me to pay closer attention to what is available in the way of visiting speakers and performers.

LikeLiked by 1 person